Dearest readers and loving supporters- Here is another part of my terrible week. If you missed the last entry - read here.

I manage to remain both lucky and unlucky at the same time.

Part 3 - Emergency Surgery

A kind nurse in her colorful pastel surgical scrubs prepped me in the operation room. She had a pin with the character Keroppi the frog on her badge. As a kid, I’d doodle him in my school notebook.

His wide bulging eyes saying, “Good luck, lady!”

The team introduced themselves with urgency. I tell the anesthesiologist how I’ve been unable to awaken from anesthesia before, trapped in the dark. He reassures me that he’s read that in my chart and they’ll be ready.

Nate, my surgeon, approaches me and introduces himself in a friendly “let’s do this” manner.

I stopped the commotion and gurgle through the NG Tube, “Let me show you what really matters to me right now.”

I take out my phone and show them all a picture of July.

“Please take care of me. I need to get home to her,” I say as strongly as I can, tearing up.

“We’ve got you,” Nate says smiling behind his mask without hesitation.

And then in moments, I have no more memory.

I wake up later in the day with Zach sitting by my side. This is most comfortable I’ve felt in days. A numbed exhaustion hovers over me as he tells me the procedure went well.

Through three laparoscopic incisions, they lysed the scar tissue bands tying up my bowels, as well as a couple more that seemed potentially problematic and they pulled the twisted track of my stomach apart. Luckily, the tissue returned to a healthy color once untied and I didn’t need a bowel re-sectioning or colostomy bag.

They take me to a room on the very same post-op floor I volunteer on each week.

The room is almost identical to the one I’ve had previously, except the art is different. On the wall is a print of one of Roy Lichtenstein’s interior living rooms.

The first day post-op, I manage quite well and even walk for the first time. I don’t even mind not eating or drinking. None of that is allowed until all my body’s bile and fluids have been sucked out of my nose.

But as the operation’s anesthesia begins to leave my body - pain changes from a whisper to a roar.

But the pain isn’t from my surgery site or stomach. It’s in my throat and face.

And then I get the brutal news that my NG tube may not be positioned correctly and they need to push it down farther… and my blood pressure rises.

Dear God, not again. Please not again. Why???

A patient nurse named Jessica and a tall clinical partner hold me as they measure the inches they need to push the tube further in. I feel it now as I type these words - more bright pressure in my head, bleeding out of my nose and mouth, and sliding in my throat and neck and down inside me. Gagging and shuddering as my throat fills with the tube’s movement.

Somehow, the medical industry thinks this tube is better than vomiting constantly. The jury’s out for me.

Especially since the tube makes me wretch and dry heave so much I pull my shoulder muscle and the bleeding doesn’t seem to stop. So much so, my stomach contents are pink with blood instead of a usual greenish yellow color.

In the evening, I take my first walk with a clinical partner named Angel who feels like my Mexican Grandpa.

On the walk, I fart and Angel as well as the nurse’s station give a cheer. Best fart of my life. Passing gas is a sign of healing. My Pop-pop had a jar in his office labeled “pet fart” - I know he’s proud from heaven.

Relieved with the progress, I think, “I can get this tube out now, right????” But no one comes.

They give me a deep dose of Dilaudid - a morphine and opioid combo and I feel waves of nausea until the pain subsides and I sleep.

The next 12 hours is an agony waiting-game cycle. I’d get Dilaudid, fall asleep, wake up in pain two hours later and lay in still torment for the next two hours until my next dose was allowed.

Alone in the room before Zach arrives, I start weeping and losing my sanity. I call the nurse call button and I painfully cry through the tube in gasps.

“I’m losing my shit!” I sob into the line. “I’m in so much pain! It’s so bad.”

A nurse and clinical partner come and check on me. They look worried for me. The nurse holds my hand as I wail away, where every sob hurts more than the one before.

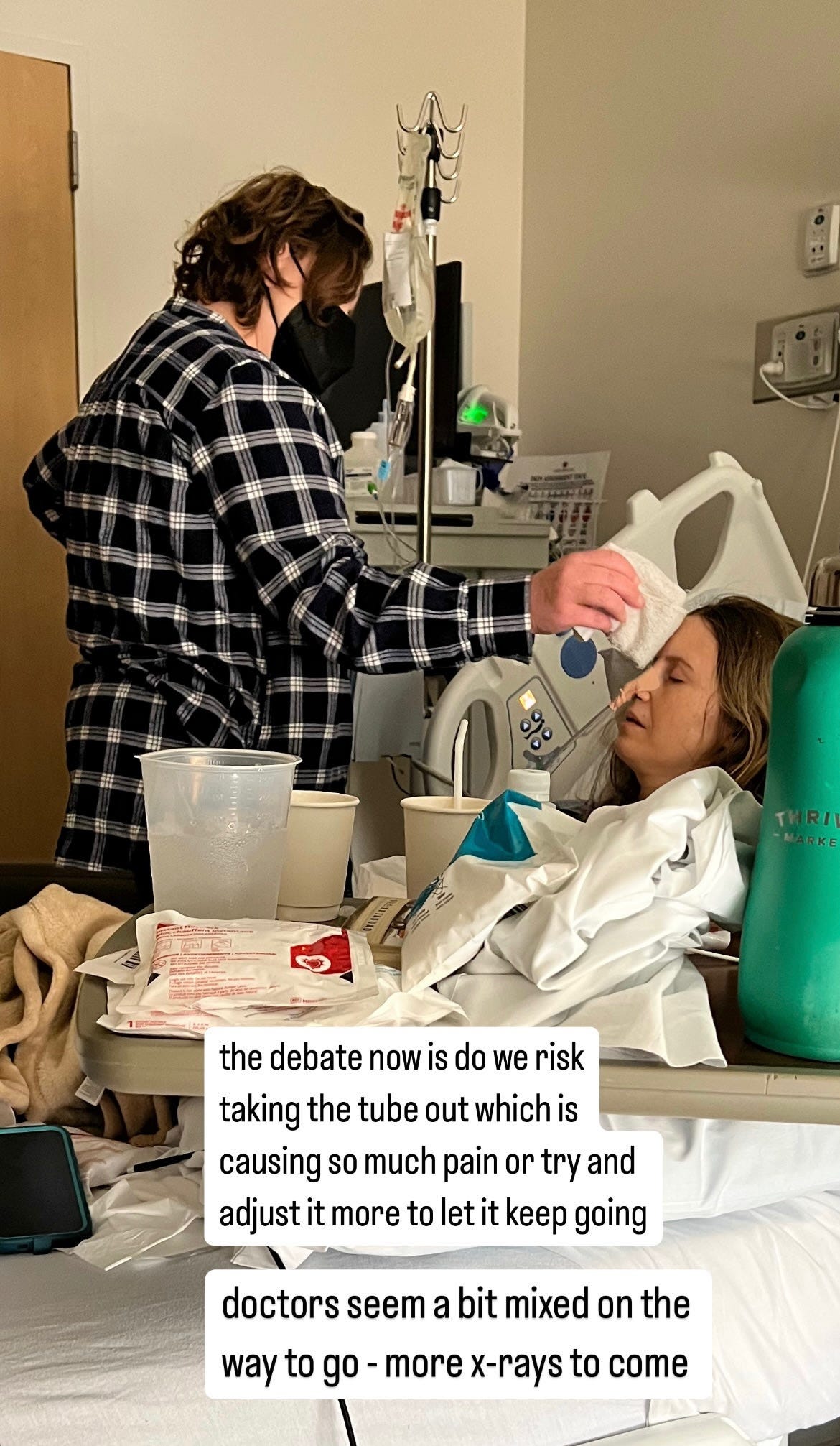

Meanwhile an entire excruciating morning goes by, and my surgery team hasn’t shown up for progress check-in or next steps. To stay sane, I swish water around my mouth and spit it out in a cup at my bedside. Zach and my dear friend, Tori, dab my head with a cool wash cloth as I lay paralyzed by pain, playing massage music on the mobile phone.

Now, remember, I know how tough I am and if I’m laid out in pain, it’s excessive. I have 100% confidence in my own assessment.

So when finally the surgery team comes through the door, I have little patience as a patient. I mention the torturous headache, saying the abdomen feels like a breeze in comparison to the throbbing in my face and neck.

“This pain treatment is not working for me. I’m getting knocked out by the Dilaudid and then in agony for two more hours when it wears off. It’s my job to heal and I can’t do that effectively if I’m either knocked out by an opiate or paralyzed in pain. And I’m really strong- I walked around for days with a bowl obstruction like it was nothing. This pain is BAD.”

“We’ll give you a smaller dose every two hours. The order is in,” one surgeon says without argument.

I express my frustration about not being seen earlier, knowing they round starting at 5am and it’s lunch time.

The seven doctors - residents and surgeons who look straight out of Central Casting - look at me compassionately. They know it’s late.

The senior doctor who stands in the back with his white coat tries to defensively explain to me how a hospital works. “There are patients who are frankly, dying.”

“You started rounds seven hours ago. I need better communication. And I’m hitting my progress goals. When can I get this tube out? I need a plan.”

I can tell this senior doctor doesn’t like me. But the feeling is currently mutual.

“Look I don’t want you to feel like we’re forcing anything on you. If you want it out, we’ll take it out,” he says gruffly, adding, “But if you were my sister I wouldn’t take it out.”

I think, if I was his sister, he would have checked on me 5 hours ago.

“I don’t want to be non-compliant, but this is not working for me.”

He looks at the tube’s contents, “I’m not convinced it’s in the right place. We need another X-ray. Have you been drinking water? People sneak it.”

I start to flip out, “I’ve had two X-rays and it’s been adjusted once already. I’m taking water in my mouth and spitting it out so I don’t lose my mind.”

They tell me they need a little more time after another more extensive X-ray to verify placement for a third time. They needed four hours, where they’ll watch what comes out of the tube without suction and decide from there

I set a timer on my phone for four hours. I pray and sleep and dry heave and drip blood and try to make excruciating time move forward.

I tell my nurse, “I just want warm tea with lots of sugar.”

I imagined myself drinking the tea and feeling the soothing warmth tumble down my throat and the sweet taste on my tongue. The longing was fierce.

Swishing the water around my mouth is such a solace in the madness - it was so hard not to swallow.

When I get this tube out, swallowing will be such joyful relief.

When I pass the stomach contents test, four hours later- it’s still another 90 minutes of waiting until I get clearance to remove the ghoulish tubing.

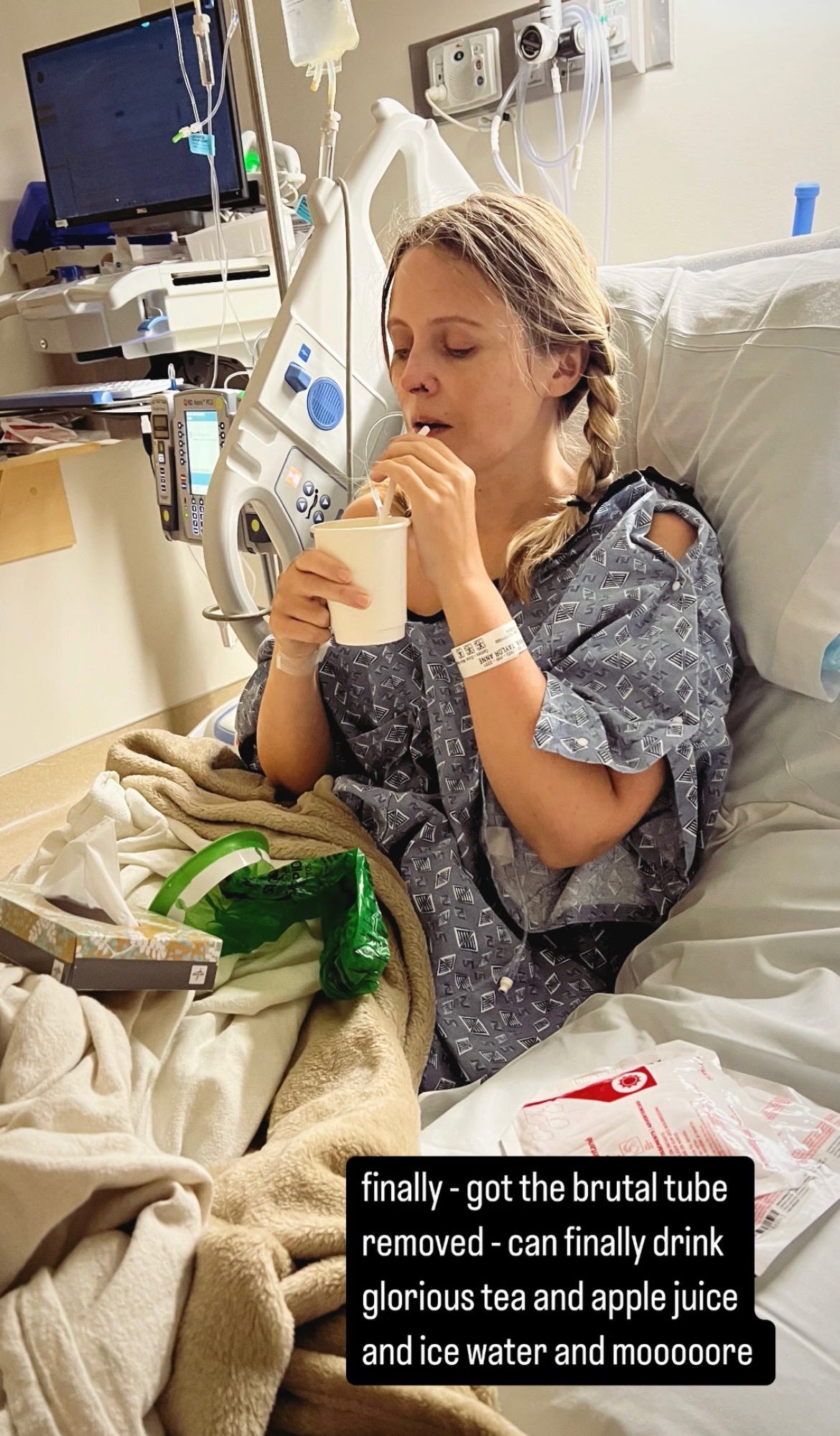

The removal of the NG tube is gruesome on a scale of what’s difficult, but it’s nowhere near as bad as the ventilator/intubation removal. As the tubing is pulled out of my body, it exited quite smoothly in comparison.

The relief washed over me, but pain still throbbed.

I sipped cool water through a straw and swallowed. The gush of cool liquid felt like mercy on my raw throat. Swallowing is heaven. I could hear angels sing in my cells.

My cautious night nurse, a big guy who looked like a line-backer, urged “Sips. Just sips.”

“Please, can I get some warm tea with sugar? A lot of sugar?”

They bring me a warm cup of chamomile full of sugar packets in a small paper cup. I hadn’t consumed anything in two days and each sip was a galaxy unto itself of pure joy.

I went to sleep with my sugar-coated solace on my tongue. I think to myself, I am past the worst of this chapter. Now, when can I see my July?

Hurdle after hurdle after hurdle - I just keep going. For her. July - my invincible summer.

To be continued here:

YOU MAY HAVE MISSED IT

Things Happen in Threes: The Psychological Thriller Part 1

Is this déjà vu? Am I close to death and seeing the future?

If you’re new here and wondering, “what happened to this lady?” read:

Welcome to my disease. What is atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS) or Complement-Mediated Thrombotic Microangiopathy (CM-TMA)?

Hi, If you’re new here, I started writing a book six months ago when I was on dialysis. It’s intended to be both memoir and a practical tool to help folks who might be going through something similar or those caregivers and family supporting someone with a challenging diagnosis. I hope to include excerpts here as I write. NOTE: This is not intended to r…

I started writing this when I was on dialysis. It’s intended to be both memoir and a practical tool to help folks who might be going through something similar or those caregivers and family supporting someone with a challenging diagnosis. NOTE: This is not intended to replace actual medical guidance. Please consult your doctors on your individual challenges and situations. Please talk to your clinicians before adjusting any of your care protocols. Also names have been changed for most of my medical staff.

Thank you to Shanti, a new paid subscriber. I’m eternally grateful! Thanks for your support!

Thank you to CC Couchois, Roy Lenn, and Dr. Richard Burwick for your founding level donation.

Oh gosh, Taylor, I'm so sorry you've had to go through all of this! I appreciate you sharing your story - I know it wasn't easy to recount. I hope things have improved, or that you're on the right track now. 🙏

Oh my god, this sounds so brutal. It's these details of a tube down the throat that they seem to gloss over and one doesn't realize how insanely awful it is. I'm floored by your courage to just make it through all this pain and still be able to talk about it. Love to you and the whole family.